By Jia Fan

(PhD Student, Department of Media and Communication, City University of Hong Kong, Eurybia Researcher)

Preface

In March 2025, with the support of City University of Hong Kong and my doctoral supervisor Professor Liu Xiaofan, I conducted a one-and-a-half-month field study in Sanxing Village (formerly Nantang Village), Sanhe Town, Fuyang City, Anhui Province. During this period, I conducted in-depth interviews with 14 participants, including core members of Nantang DAO, employees of local agricultural cooperatives, and villagers. I also participated in the Nantang DAO onboarding program, daily operations of the Nantang Xingnong Cooperative, and translation work for the Nantang Buzhi DAO translation group.

Although my time was short, I was deeply moved. I witnessed the locals’ earnest efforts to put DAO ideals into practice, as well as the many challenges they faced as pioneers in the rural-building DAO space. These issues are not only unique to their context but also reflect broader difficulties currently facing DAO development.

The "Chronicles of Nantang DAO" series is divided into seven parts: Origins, Gathering and Conflict, What Are the Goals?, Experiments in Incentives and Circulation, Is It Decentralized Enough?, Paving a New Path, and Final Thoughts. These writings aim to objectively document the stories of people striving for change on this land — the faint yet persistent light of idealism in rural revitalization, the frustrations and perseverance in practice, and the most authentic human connections. If these stories can resonate with more people or offer insights to rural builders and Web3 explorers alike, then they have fulfilled their purpose.

This installment includes Parts 6 and 7, focusing on the future direction of Nantang DAO, exploring reflections on the integration of rural development and Web3, presenting members' visions, and sharing my own grounded experiences from the field.

Paving a New Path

The story of Nantang DAO continues. Despite numerous challenges, things are still unfolding organically and emerging naturally. The community explores its way forward through trial and error, constantly seeking new possibilities amid transformation. Several core members have already traveled to Jianta Village in Pujiang County, Chengdu, attempting to launch a new project aimed at discovering the true intersection between rural revitalization and Web3 — building a "Rural Entrepreneurship DAO."

Meanwhile, Jump has chosen to remain in Nantang, proposing the initiative "Living Well Together"1. By organizing blockchain co-learning sessions and band activities among local youth, he continues to deepen community engagement. One group explores outward; another roots itself locally. Both paths proceed without contradiction.

Breaking new ground is never easy. Yet, as a saying goes: "Pessimists are often right, but optimists keep moving forward." The optimists of Nantang DAO are now writing their own answers through action.

Attracting More Professional Talent

Talent is the foundation of any organization’s growth. Cikey once reflected that in its early days, Nantang DAO failed to effectively attract professionals who truly understood blockchain and Web3. Compounded by a general lack of rural development experience among early members, the community encountered many avoidable detours during its exploration phase.

Fortunately, this gap has since been recognized, and a series of improvements have been implemented. Currently, Nantang DAO plans to invite senior experts from the industry to form a “Nantang DAO Governance Advisory Group”, offering professional mediation for internal disputes and providing systematic strategic guidance each quarter.

Additionally, through the “Bilateral Enlightenment Plan for Rural Development and Web3”, community members have repeatedly participated in domestic and international Web3 events and university outreach programs. These experiences have not only enhanced their professional understanding but also attracted more individuals passionate about both Web3 and rural revitalization.

This two-way interaction has opened up new opportunities for talent recruitment. Excitingly, new members continue to join, bringing fresh energy to the community. Some excel in artistic creation, adding creativity to rural cultural activities; others specialize in branding, supporting Nantang DAO’s external communications. A few have strong backgrounds in organizational research, contributing valuable insights to governance mechanisms. These new members not only bring technical expertise but also open up new horizons for Nantang DAO’s long-term development.

Facing the World, Learning from Experience

What are the real needs of rural communities? Can Web3 inject new momentum into rural development? How can DAOs truly take root — is this merely a question for Nantang, or a shared global challenge?

Nantang DAO has studied multiple international DAO cases, some of which offer valuable insights for rural revitalization. For instance, in response to post-earthquake reconstruction and an aging population, Japan’s Yamakoshi Village (Yamaguchi-mura) launched the "Nishikigoi NFT" — centered around its famous local specialty, the Koi fish — and treated NFT holders as "digital villagers."

This initiative formed a DAO-like community that attracted over 1,750 global participants and raised funds to support regional sustainability. Although this model did not incorporate typical DAO elements such as smart contracts or on-chain treasuries, it effectively addressed local challenges.

The experience of Yamakoshi Village offers meaningful inspiration for Nantang DAO. Recently, the village further proposed a vision called the “Two-Layer DAO Governance Revolution”:

- The Yamakoshi DAO2 serves as a governance body where both physical and digital villagers co-govern through voting on Snapshot.

- The Sewaribito DAO functions as a platform for cross-regional collaboration (e.g., with Hekiryo Village and Tenryu Gorge), aiming to build a LocalDAO Network.

This dual-layer structure bears striking resemblance to Nantang DAO’s current developmental trajectory, and could serve as a valuable reference model for its future evolution.

Figure 1 - Keio University SFC Study Group: "Understanding the Digital Village System through the Yamakoshi Village Case"

Figure 1 - Keio University SFC Study Group: "Understanding the Digital Village System through the Yamakoshi Village Case"Another relevant case is CabinDAO — a decentralized autonomous organization dedicated to building networked cities through community collaboration and technological innovation. Its development can be divided into four phases3:

- 2020–2021: The Creator Era — Established the Creator Cabins program, which focused on funding creative residencies for artists and builders.

- 2021–2022: DAO Service Phase — As DAOs flourished globally, CabinDAO entered a service-oriented stage. During this period, the community built multiple DAO media brands and developed tools such as on-chain and physical passport systems for digital communities.

- 2022–2023: Digital Nomad Focus — Amid crypto market turbulence, the team significantly downsized but shifted focus toward creating natural, off-chain communities for digital nomads, and began building a global co-living network.

- Early 2024: Family-Centric Communities — The keyword became "family communities." The team decided to deepen its connection with local communities by launching the Neighborhood Accelerator Program, proposing the creation of a community where people live near friends and collectively raise children.

Figure 2 - CabinDAO Roadmap

Figure 2 - CabinDAO RoadmapWhat’s worth learning from and reflecting on is that after years of continuous exploration, the Cabin team came to believe they were better suited as a loose community network rather than as a startup or DAO. On May 8, 2025, Cabin officially announced its dissolution on the X platform5, deciding to abandon DAO funding and commercial projects in favor of becoming a purely community-driven network.

This decision stemmed from a deep reflection on the different models of entrepreneurship, DAOs, and community networks:

"Venture-backed startups are best suited for small, focused teams capable of rapid pivots in search of short-term, financially viable high-growth opportunities. DAOs function best as trusted, neutral governance mechanisms for distributing ecosystem grants from existing revenue streams. Community-driven networks are most effective as loosely connected organizations, allowing many individuals to independently explore adjacent paths and build what they find most interesting and valuable."

For practitioners of rural-building DAOs, the question of how to position DAOs within rural communities, and what value DAOs bring to local development, remains a shared global challenge.

Rooting in the Local, Seeking Strength

While learning from global pioneers, Nantang DAO must conduct in-depth local research and analysis to determine how it can truly root itself in the community. To develop practical goals and an actionable roadmap, the organization needs a comprehensive assessment of local resources — including economic conditions, human capital, cultural values, political structures, social capital, geographic advantages, and natural environment.

Nantang Village has long been known for its historical experience with democratic governance — and social engagement remains its greatest asset. Looking back at Nantang’s history, one can clearly see that the pursuit of democracy and rights has never ceased. Its key historical milestones have always resonated with progressive organizational ideas within broader societal movements:

- From the late 1990s to early 2000s, amid rising civic activism, movements such as citizen legal advocacy and environmental protection emerged, empowering people to defend their rights through collective action.

- Nantang began organizing farmers' rights protests and promoting grassroots elections and self-governance.

- From 2003–2004 onward, the goal of farmer organization gradually shifted from protest toward constructive development. As Yang Yunbiao reflected: "In the past, we fought for rights from a confrontational stance; after establishing the cooperative, our daily work became about defending rights through livelihood development, cultural construction, and rural self-governance."6

- Later, during the process of farmer organization, Western practices were introduced — most notably Robert's Rules of Order — which were localized and implemented in 2008. This phase saw rapid growth in the village’s economic and cultural sectors.

During a rural development dialogue, Yang Yunbiao once emphasized: "Rural revitalization is not just about industrial or organizational revival — it must return to the idea of 'human revitalization,' asking how people can live with smiles on their faces and dignity in their hearts."7 Today, the formation of Nantang DAO continues this tradition of organizational innovation — marking the latest attempt to integrate rural ethics with modern civilization.

From rights protection organizations to procedural rules, from cooperatives to Nantang DAO — despite the different forms of democratic organization attempted in Nantang, the past 30 years have brought dramatic transformation. Yet, it's important to recognize that no matter how innovative the organizational form may be, the core focus must remain on human connection — addressing the fundamental needs of local villagers.

Encouragingly, ongoing initiatives have already generated meaningful connections. After living and working together for some time, members from both the DAO and the cooperative have begun forming real bonds. During my fieldwork, I observed local youth using Robert’s Rules of Order spontaneously when facing difficulties in group meal coordination — proposing and seconding motions to efficiently reach consensus on task assignments.

I also witnessed the budding awareness of equality among local youth. They are starting to organize themselves independently, reflecting critically on issues like lack of transparency in decision-making, unclear responsibilities, and ambiguous rules regarding rural life and work. The emergence of independent thinking and critical consciousness will become a valuable asset for Nantang’s future.

On the other side, the cooperative is also broadening its perspective — planning to build a "third space" aimed at attracting digital nomads, fostering deeper connections with younger groups. By acting on the basis of mutual understanding and respect, new possibilities may emerge from this land.

Final Thoughts

Despite existing conflicts, the integration of rural development and Web3 holds great promise. Over time and through practice, both sides may gradually find common ground amid differences, eventually shaping a governance model that balances individual autonomy with collective collaboration.

As Nantang DAO moves forward, while promoting Web3 technologies and decentralized governance models, it must deeply root itself in the local culture and the real interests of villagers, focusing on solving the most pressing rural challenges. Only by doing so can these new digital tools truly touch the soul of rural society.

How Should We View DAO Experiments in Rural Areas?

Rural development and DAOs resemble two initially tangent circles: one carries the practice and sentiment of rural revitalization, while the other reshapes trust and collaboration mechanisms through decentralized technological principles. In recent years, these two fields have begun to intersect, attracting Web3 practitioners dedicated to rural development and rural builders eager to embrace new technologies.

However, due to short exposure time and differences in values and cultural backgrounds, this intersection inevitably brings friction — from clashes between decentralized governance logic and rural collectivist culture, to tensions between foreign ideas and local traditions.

The central question is: as a new form of organization, where does DAO fit within the rural governance structure? What are its scope and capacity limits?

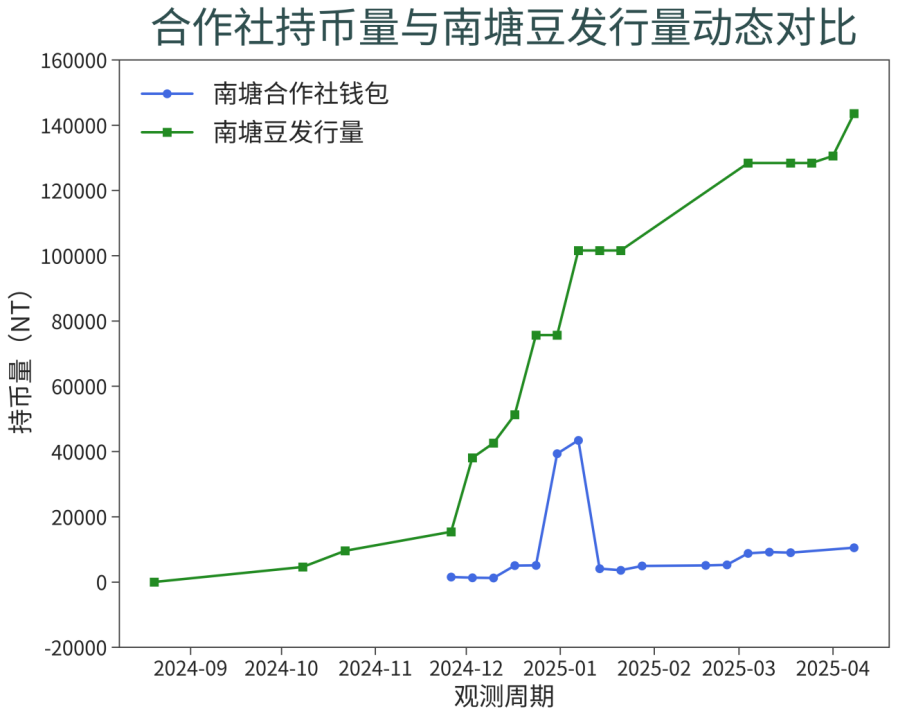

Taking Nantang DAO as an example, if the issuance of Nantang Beans is merely a digital replication of traditional rural governance incentive systems like the labor-hour system — and even fails to surpass the usability and accessibility of existing alternative currencies8; if token-based voting is just direct democracy relocated to a Web3 platform, effectively excluding villagers from real participation — then how much change can such so-called "organizational innovation" truly bring to rural society?

Though framed around Nantang DAO, these questions are not unique to it. They represent broader challenges for all future rural-building DAOs or similar initiatives.

Moreover, we must acknowledge that DAO is not the ultimate solution to all organizational governance issues9. No organizational design is perfect — the key lies in the trade-offs and decisions made during the governance process, which ultimately determine whether an organization can meet sustainability challenges.

Organizations vary in strengths and weaknesses — they coexist rather than replace each other. If we view decentralization and autonomy as a spectrum, historical organizations — and different stages of the same organization — fall at various points along this continuum.

Many DAO failures stem from a lack of understanding of this complexity:

- Some aim to build commercial projects but find centralized structures more efficient.

- Some attempt to distribute funds via DAO, yet most members aren’t true beneficiaries — economic support often gets monopolized by a few.

- Some DAOs focused on community building struggle to define their role.

A vivid example is the Uniswap Foundation’s decision — made through a DAO vote — to allocate $165 million in liquidity mining rewards for Uniswap v4 and Unichain, which sparked outrage among members. Critics questioned why the foundation was spending money when Uniswap Labs (a centralized entity) earned millions from front-end fees.10

Therefore, rather than chasing after the ideal of a perfect DAO, rural development practitioners should focus on practical questions:

- Under what circumstances is organizing via DAO necessary?

- Where exactly lie the boundaries of DAO?

- Which decisions benefit from collective deliberation, and which require decisive leadership?

Although there may be no standard answers, and perhaps a truly pure DAO can never be fully realized in practice, idealists can still take comfort in knowing that the core values pursued by DAOs — transparency, participation, and decentralization — serve as a powerful driving force behind the continuous evolution of human organizational forms.

Is Decentralized Governance Suitable for Nantang?

Nantang may not necessarily need an externally introduced DAO, but the ideals of DAO — transparency, participation, and decentralization — undoubtedly offer valuable insights for improving cooperative governance.

By drawing upon these external experiences, Nantang can gradually introduce decentralized governance mechanisms while preserving its unique identity — paving the way for more resilient and inclusive development.

Take the mutual fund program as an example: some villagers expressed dissatisfaction during interviews about how cooperative funds were invested in certain “local elites.” Had a decentralized decision-making mechanism been in place — allowing villagers to collectively decide fund allocation through voting — perhaps the tragedy could have been avoided or mitigated. Even if such grievances emerged only in hindsight, they reflect a sense of alienation from the decision-making process.

Decentralized governance not only enhances community participation, but also improves fairness and rationality by distributing risk across the group.

During my fieldwork, I observed that the current operational model of the cooperative affects every aspect of its activities — including the intern program — creating an awkward middle ground: lacking both the rigorous rules and efficiency of corporate governance, and the grassroots dynamism of self-organized communities.

In this context, Nantang faces a critical choice between hierarchical and decentralized models:

- Fully adopt a hierarchy: Clearly define Biao Ge as CEO, Liu Bing as board member and investor, and establish a clear chain of command.

- Experiment with multi-centered governance: Delegate decision-making power over small-scale projects to interns or full-time staff, while Biao Ge and Liu Bing focus on resource provision and strategic guidance.

This second approach has the potential to unleash creativity within the team while maintaining essential coordination and support.

The Expectations of Nantang DAO Members

The final question I asked during my interviews was about members’ hopes for the future of Nantang DAO and its next steps. Below are some of their responses:

Bixing emphasized the importance of continuous change and openness, encouraging broader participation to drive Nantang DAO forward.

"Change is inevitable. We must constantly seek transformation and open up new fronts — both in terms of thinking and action."

He believes that integrating different groups is a major challenge:

"Bringing together two very different kinds of people and aligning them toward a common goal is already a huge task."

By expanding participation, he hopes to increase influence:

"The more people involved, the better known we become, and the more people we can attract."

Biao Ge expressed confidence in the future, emphasizing the central role of people and urging a focus on practical action.

"It’s not that I wish for Nantang DAO to disappear — because I’ve benefited from it too,"

"I just hope they can do things with real impact."

He stressed the importance of personal well-being:

"People should take care of their bodies and minds. If Web3 participants burn out, fall into depression, or even forget how to enjoy a good meal, then what’s the point of Web3?"

Cikey hoped that people could "live happily and play joyfully."

"At least this narrative can inspire and nourish people. Doing something meaningful in the countryside is always a good thing."

Pianpian advocated for grounded actions:

"We should do things that are local and concrete — not too abstract or distant."

Jump admitted he never felt full identification with Nantang DAO:

"From the beginning, we were never really a team."

"I needed to trust someone to work effectively, but some relationships never built that trust."

He suggested that the best possible outcome for Nantang DAO might be as "a platform for fund distribution," while actual projects would benefit from smaller, tightly-knit teams.

Xiao Bai expressed concern over current trends:

"Many members feel that Nantang is no longer suitable for their development. To be honest, I’m worried — and there may eventually be a split."

He hopes that Yunxiang DAO can become a like-minded partner of Nantang DAO:

"Collaboration between us would be a great thing."

But he opposes the idea of one DAO "incubating" the other.

Yu Xing focused on reducing internal friction and moving toward real-world integration between Web3 and rural development.

"We need to help those who want to build avoid getting stuck in endless debates — our ultimate goal is to create order from chaos and actually get things done on-chain."

He believes the exploratory phase has ended:

"We can’t stay in exploration forever."

"We’ve already created an impact through rural-web3 integration — now it’s time to move beyond exploration and start doing real work."

My Reflections

As I write this conclusion, I have completed my time living and conducting fieldwork in Nantang. If I gained anything during this period, it was a set of genuine and profound reflections.

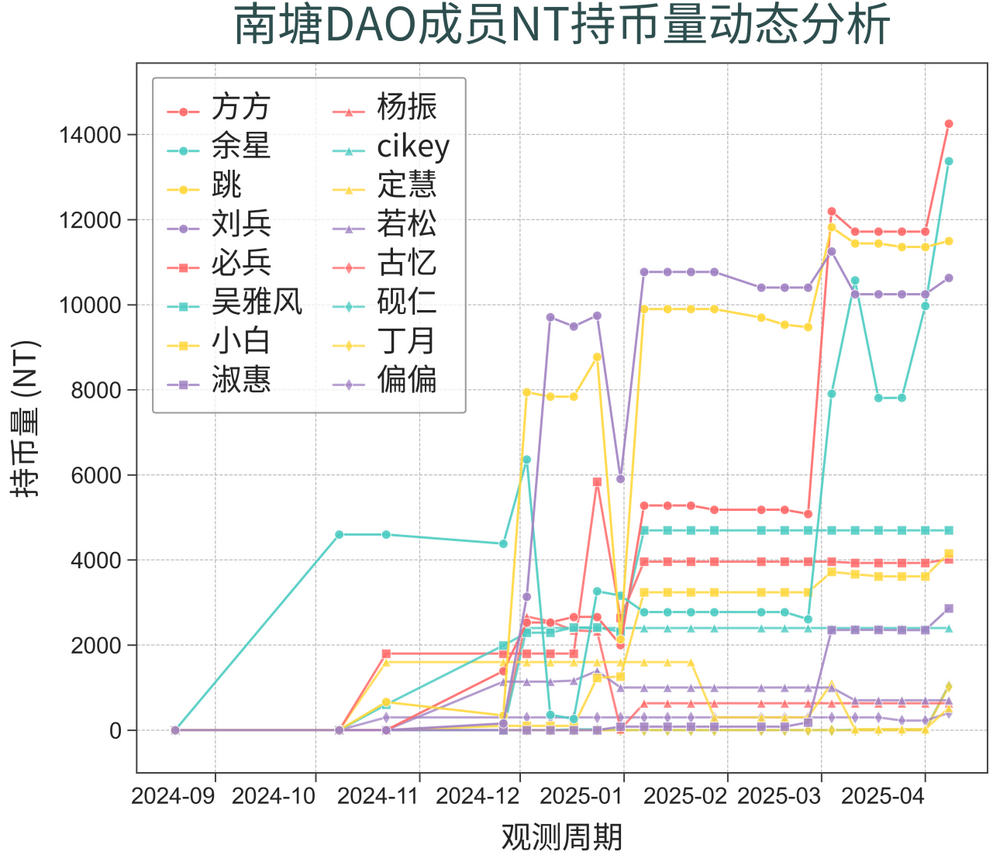

While analyzing the token holdings of Nantang DAO members, I came to understand that the meaning of data analysis goes far beyond revealing just "significant differences." Each shift in numbers represents a vivid story — a life unfolding behind the scenes.

I witnessed many people arriving with high hopes, earning their first tokens through community contributions; I observed how Liu Bing, the main financial supporter, was somewhat “forced” into being granted voting rights; and I was deeply moved by the collective effort of members who used real actions to support local creditors in need.

Of course, I also saw some people selling off all their Nantang Beans, or choosing to leave the community altogether — no longer participating in any transactions.

Here in Nantang, I temporarily set aside theoretical models and causal frameworks, and for the first time, truly felt the joys and sorrows of each individual behind the data.

Perhaps I will still feel anxious about completing my Ph.D. and publishing my dissertation — but at least when looking at this dataset, my heart feels grounded.

Re-evaluating the Meaning of DAO

At the beginning of this journey, my interview guide was filled with grand themes: organizational structure, mission statements, future development paths — perhaps overlooking the most basic aspect: human relationships.

In essence, a DAO may carry no intrinsic value. Decentralization might be nothing more than an ideal pursuit within human society. Concepts like autonomy, self-governance, and automation remain vague — almost like semantic games.

Yet when a group of people declare their intent to build a village using DAO principles, they are expressing something deeper — a value system and aspiration:

- That rural communities deserve serious attention,

- That people can form better connections,

- That working together — whether through action or discussion — has the power to rebuild relationships among individuals.

From this perspective, Nantang Buzhi DAO may actually be closer to the true spirit of DAO in rural China than Nantang DAO itself.

Especially when most of Nantang DAO’s core members moved to Chengdu to explore new opportunities, Nantang DAO launched the “Live Well Together” proposal — aiming to better organize people's lives — which may reflect the deeper purpose that DAO should embody.

During interviews, I often asked participants:

"Is it DAO that needs the countryside, or is it the countryside that needs DAO technology?"

Now, I believe the answer lies elsewhere — neither the countryside nor DAO inherently needs the other. What we truly need is the people here, and the connections they build among one another.

Beyond Research

Though I initially came to this land with the goal of studying DAOs, what I took away went far beyond academic research.

As a volunteer in the cooperative, I met people from vastly different backgrounds:

- Some came determined to settle down and learn ecological agriculture;

- Others, tired of city life, sought peace and solace in the countryside;

- And some arrived with confusion, searching for direction amidst the intersection of land and humanity.

This was a highly diverse group — coming from all over China:

- From Guangzhou to Liaoning, Guizhou to Zhejiang;

- Among them were billionaires and those burdened with debt;

- Hong Kong’s top university postdocs and lifelong farmers — people who literally live with their backs to the sky and faces toward the soil.

Why did they come? I believe it was because of the openness and inclusiveness of this place, the villagers’ deep respect for rules and order, and most importantly, the enduring spark of idealism shared among these individuals.

Thank you to Liu Bing, Biao Ge, Jump, Yu Xing, Bixing, Pianpian, Shuhui, Xiao Bai, Jianqiao, Yang Zhen, Fangfang, and Cikey, as well as creditor Old Chang and Old Liu, for taking the time to chat with me and share your stories and feelings.

Thank you to Zhang Dong, Gan Yu, Baoshi, Keyi, Zhaolin, Jiale, Hanbai, Wenliang, and Jingyi, for co-living with me and making this period of time so fulfilling and meaningful.

Figure 3 - Local Partners Participate in the Hackathon Bonfire Night (2025.3.16)

Figure 3 - Local Partners Participate in the Hackathon Bonfire Night (2025.3.16) Figure 4 - The Band and Children of Dadi Study (2025.4.13)

Figure 4 - The Band and Children of Dadi Study (2025.4.13) Figure 5 - Morning Exercise: Web3 From the Soil (2025.4.6)

Figure 5 - Morning Exercise: Web3 From the Soil (2025.4.6)Notes and References

1https://snapshot.box/#/s:ntdao.eth/proposal/0x69407f6f76fc6977f1d5217dc83cf997376e8a8b733db5eae92a82610b0f5890

2https://www.x-dignity.kgri.keio.ac.jp/news/738/

3https://forum.cabin.city/t/cabin-labs-2025-roadmap-planning-kickoff/291

4https://x.com/cabindotcity/status/1920220527530225764

5Yang Yunbiao: Operational Democracy [EB/OL]. China Urbanization Website – China’s Urbanization Portal, 2015-03-20 [2023-11-01]. http://www.ciudsrc.com/webdiceng.php?id=82806

6He Huili, Xu Hancheng, Wang Sixian. Conversations with Rural Builders: A Real Journey to the Rural Utopia [M]. Beijing: Oriental Press, 2023: 277-295

7The concept of "alternative currency" can be traced back to Canada in the 1980s when it was initially proposed by progressive intellectuals as a social experiment tool to address economic inequality and financial exclusion. Its core idea is to construct a medium of value exchange independent from the traditional financial system, serving vulnerable groups who struggle to access formal currencies and exploring more inclusive economic models.

8Zhou Xueguang. Ten Lectures on Organizational Sociology [M]. Social Sciences Academic Press, 2003.

9https://substack.chainfeeds.xyz/p/hodl-dao-defi-obol-eth-staking

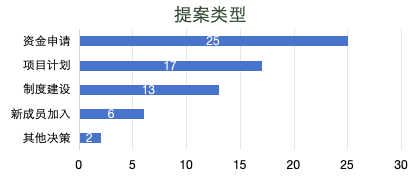

Figure 1 - Proposal Types

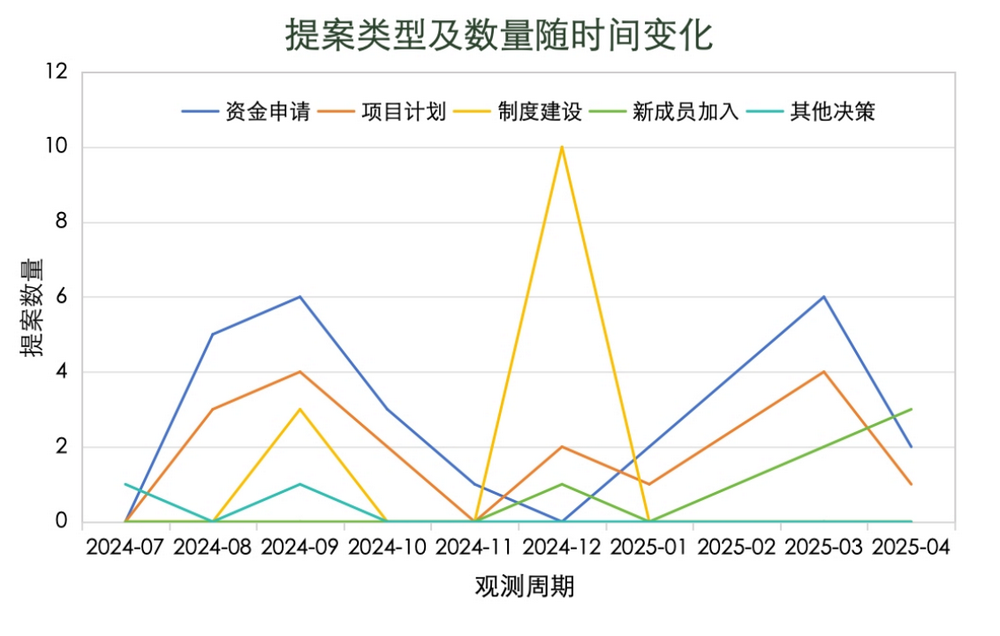

Figure 1 - Proposal Types Figure 2 - Proposal Trending

Figure 2 - Proposal Trending Figure 3 - NT Holding Trending

Figure 3 - NT Holding Trending Figure 4 - NT Issue Trending

Figure 4 - NT Issue Trending Figure 5 - NT Holding Trending

Figure 5 - NT Holding Trending Figure 1 - The Horse-Head Wall of the Nantang Cooperative Courtyard

Figure 1 - The Horse-Head Wall of the Nantang Cooperative Courtyard Figure 2 - Logos

Figure 2 - Logos Figure 3 - The Seven Founders of Nantang DAO (Source: Nantang DAO homepage[^18])

Figure 3 - The Seven Founders of Nantang DAO (Source: Nantang DAO homepage[^18]) Figure 1 - Newspaper

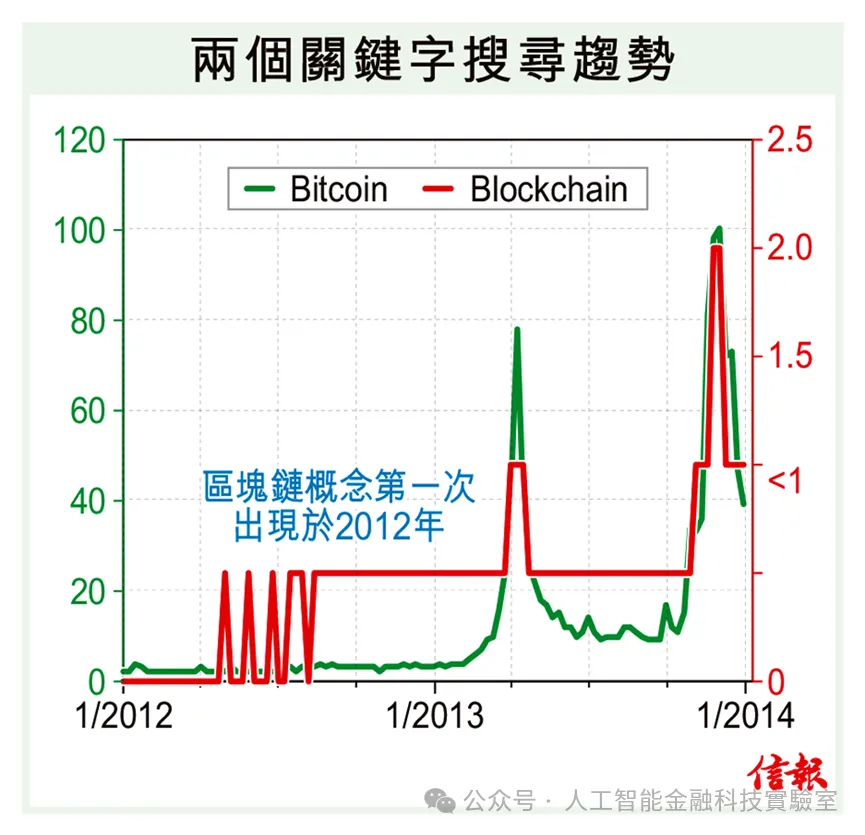

Figure 1 - Newspaper Figure 2 - Google Trends

Figure 2 - Google Trends Figure 1 - Spectrum of Five Types of OrganizationsNote: From bottom to top: Red, Amber, Orange, Green, Teal organizations.

Figure 1 - Spectrum of Five Types of OrganizationsNote: From bottom to top: Red, Amber, Orange, Green, Teal organizations. Figure 2 - Complete Decision-Making Process in a Typical DAONote: Starred steps indicate necessary steps. Parentheses contain common governance platforms.

Figure 2 - Complete Decision-Making Process in a Typical DAONote: Starred steps indicate necessary steps. Parentheses contain common governance platforms. Figure 3 - Categories and Examples of DAOs

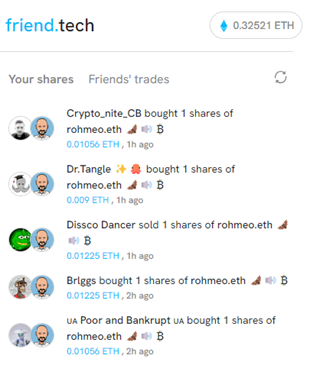

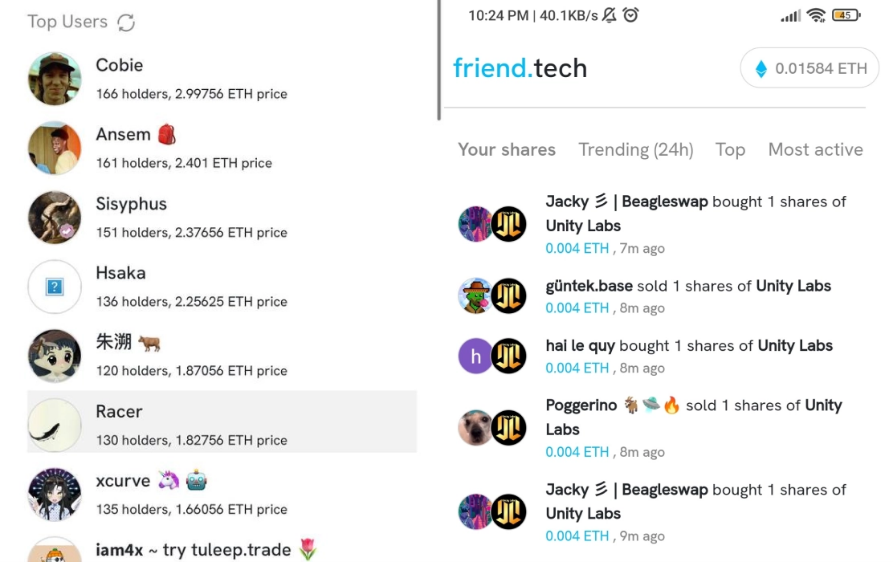

Figure 3 - Categories and Examples of DAOs Figure 1 - Application Interface

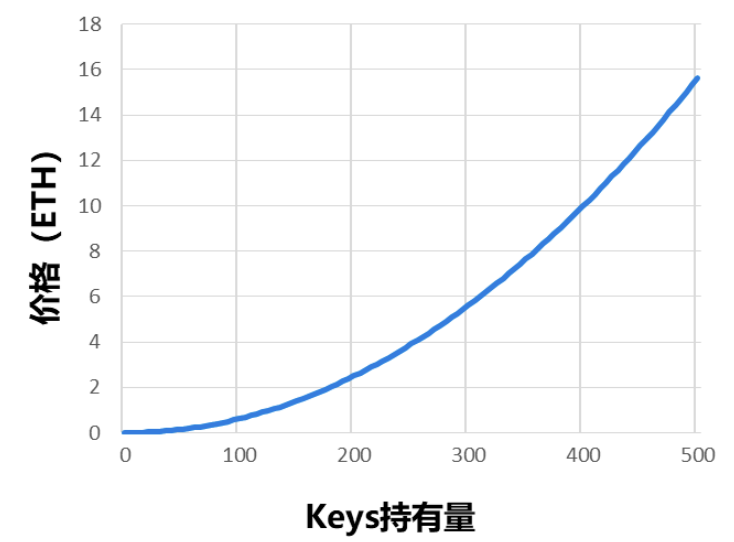

Figure 1 - Application Interface Figure 2 - The Relationship Between Keys Holdings and Price (ETH)

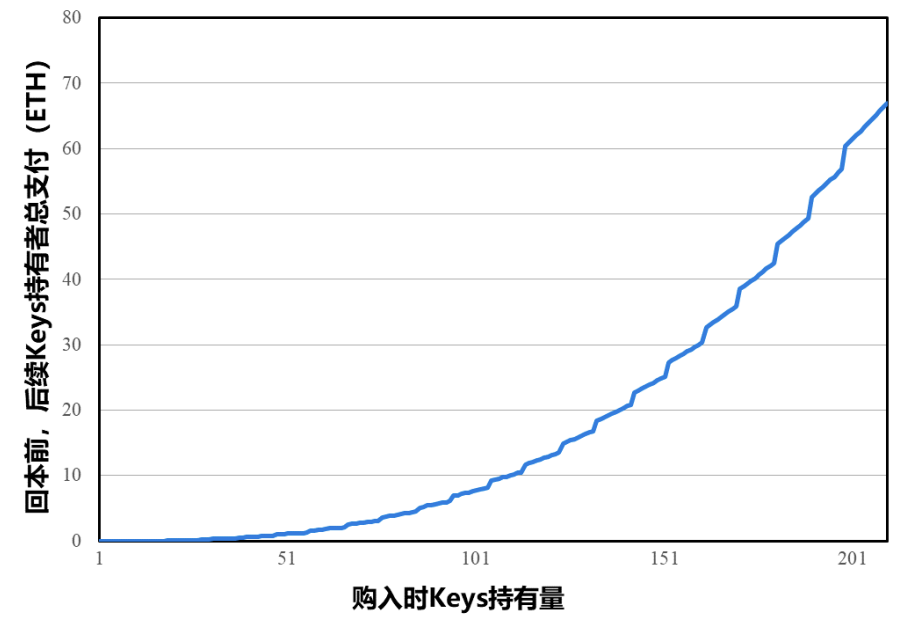

Figure 2 - The Relationship Between Keys Holdings and Price (ETH) Figure 3 - The amount of subsequent user payments required to achieve a paper profit after purchasing Keys at different times.

Figure 3 - The amount of subsequent user payments required to achieve a paper profit after purchasing Keys at different times. Figure 4 - Project Daily Transaction Count and Trading Volume (as of September 19, 2023)

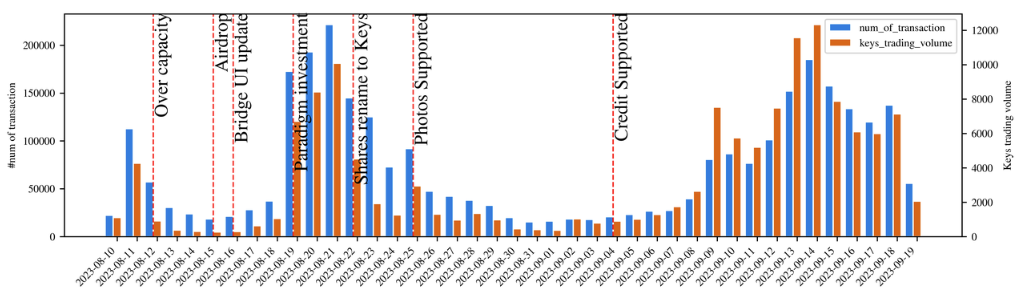

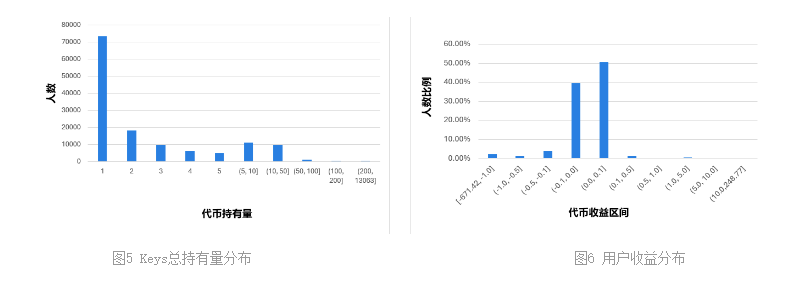

Figure 4 - Project Daily Transaction Count and Trading Volume (as of September 19, 2023) Figure 5 - Distribution of Hold and Profit

Figure 5 - Distribution of Hold and Profit Figure 6 - Top 20 Users by Total Earnings (ETH)

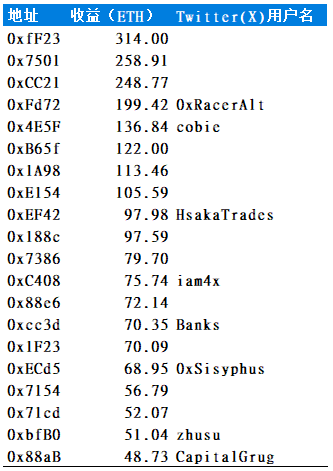

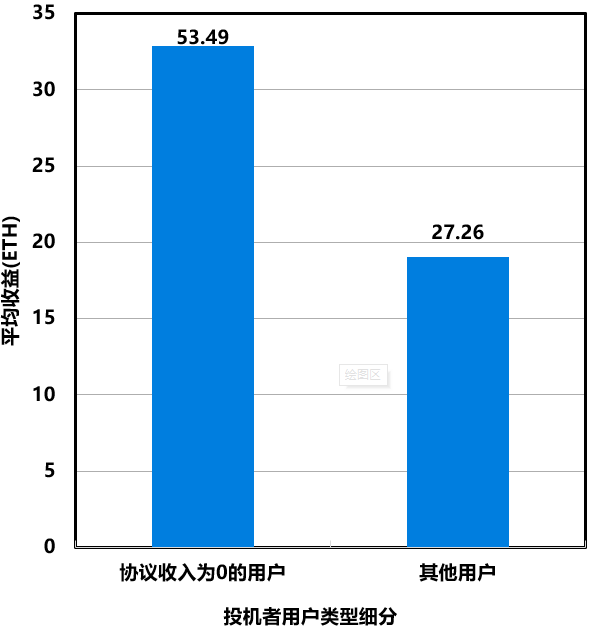

Figure 6 - Top 20 Users by Total Earnings (ETH) Figure 7 - Comparison of Total Earnings Between Users with Zero Protocol Revenue and Other Users

Figure 7 - Comparison of Total Earnings Between Users with Zero Protocol Revenue and Other Users Figure 9 - KOL Account

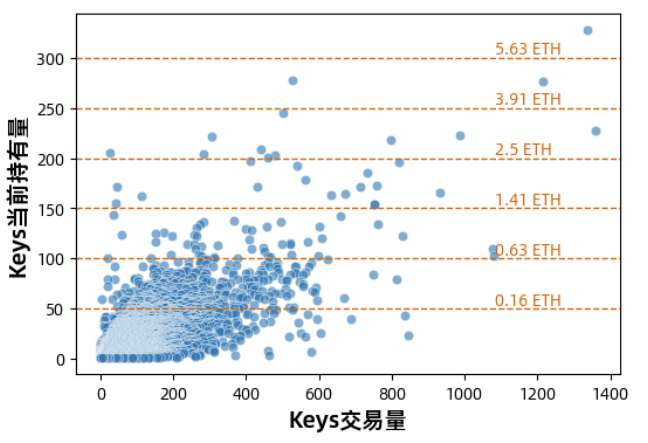

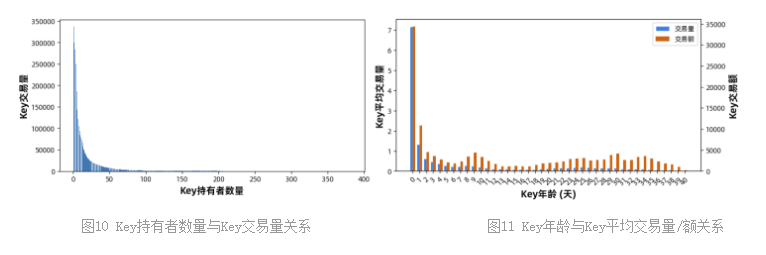

Figure 9 - KOL Account Figure 10 - Relationship Between Keys Trading Volume and Current Keys Holdings

Figure 10 - Relationship Between Keys Trading Volume and Current Keys Holdings Figure 11 - Holders, Trading Volume and Key Age

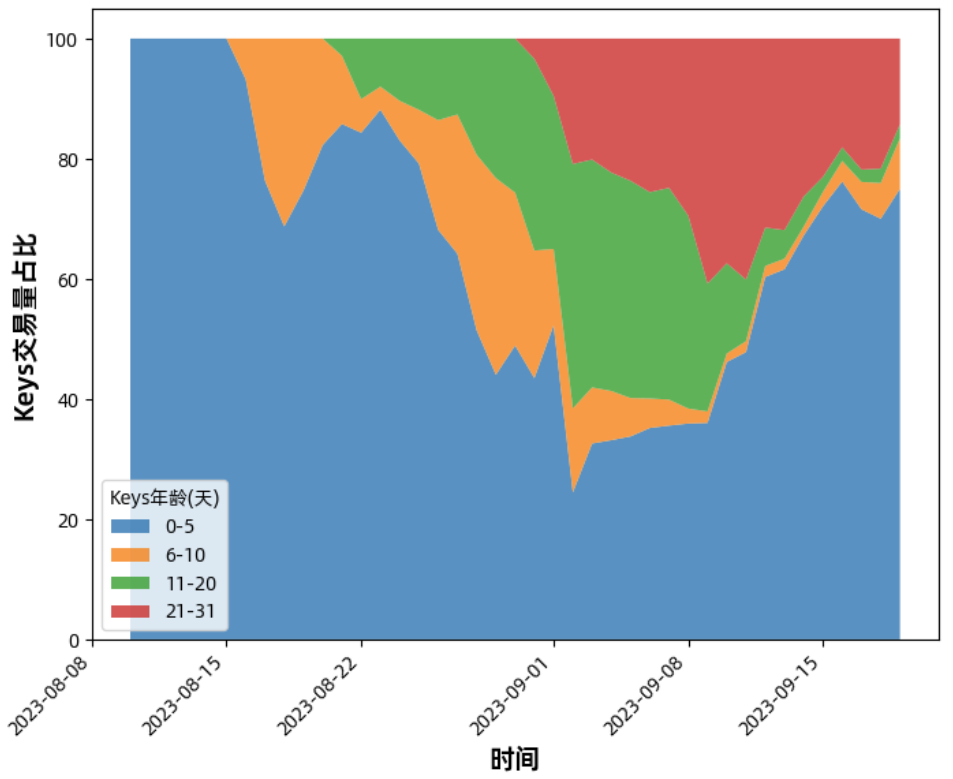

Figure 11 - Holders, Trading Volume and Key Age Figure 12 - Proportion of Keys Trading Volume by Keys Age Type Over Time

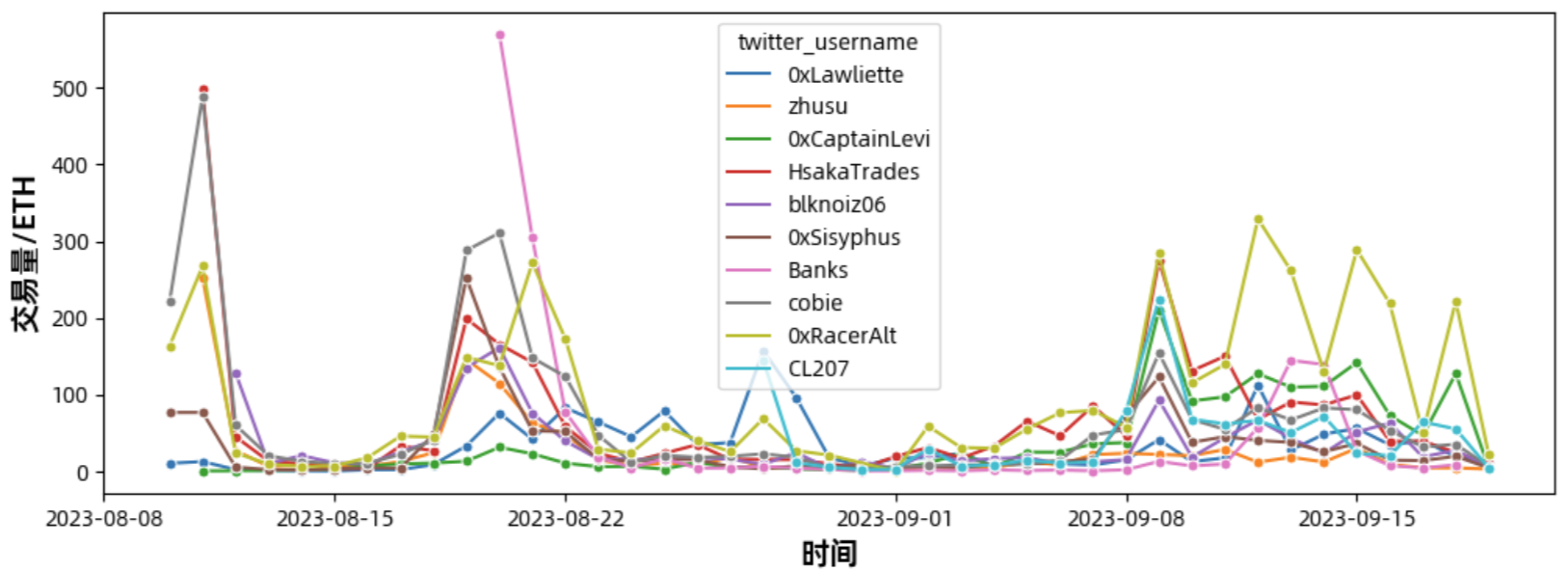

Figure 12 - Proportion of Keys Trading Volume by Keys Age Type Over Time Figure 13 - Top KOLs' Keys Trading Volume Over Time

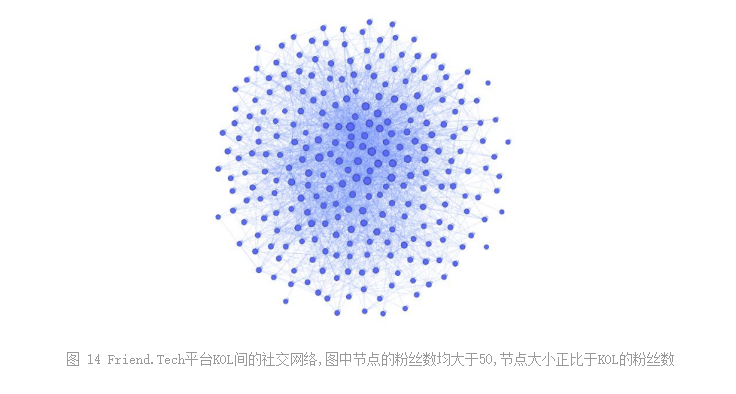

Figure 13 - Top KOLs' Keys Trading Volume Over Time Figure 14 - The social network among platform KOLs, where each node represents a KOL with more than 50 followers, and the size of each node is proportional to the number of followers.

Figure 14 - The social network among platform KOLs, where each node represents a KOL with more than 50 followers, and the size of each node is proportional to the number of followers.